Homes For Heroes and the Addison Act | A History of UK Housing

-

by Trevor Yorke

Trevor Yorke is an experienced author and artist who specialises in period architecture. For more information and to see a selection of his books you can visit his website, here.

Homes For Heroes and the Addison Act

In late 1918 while the British public was celebrating victory on the battlefield the authorities were already turning their attention to a problem much closer to home; housing the masses.

Even before the First World War slum housing had been an embarrassing issue which governments, entrenched in a Victorian doctrine of self-help, had done little to resolve.

The conflict itself had brought home the scale of the problem when thousands of men who lived in these squalid conditions had been rejected by the Army as they were not fit enough to fight.

To make matters worse there would now be hundreds of thousands of men returning from the horrors of the Western Front who would expect the country to reward them for their heroic efforts.

The Russian Revolution of the previous year was a reminder of what could happen if those in power ignored their plight. As a result one of the first actions of Lloyd George’s government was to promise to provide ‘homes fit for heroes’ and under the Addison Act, his government put in place powers and funding for local authorities to take the lead in the matter.

The inter-war years became a period of experimentation with inventive new forms of building, stark modern styles and thoughtful town planning which would help shape 20th-century housing.

Affordable Housing

The major problem in providing affordable housing for the poorest in society was the cost of building which made rents too high. Before the war, most developments were small in scale using safe, traditional methods of construction which tended to keep them out of the reach of many working families.

Now, new forms of construction were experimented with including houses made from reinforced concrete or iron panels in an attempt to lower costs.

Government grants were introduced and these new council estates were built on a large scale so materials could be bought in bulk to make materials cheaper.

With the effects of agricultural depression still affecting many areas, local authorities were able to snap up farmland surrounding many towns and cities on the cheap.

This allowed them to erect their new estates with blocks of low rise flats, rows of terraces and semi-detached houses set on spacious plots along tree-lined streets or around open green spaces.

New Construction Methods

These new houses were built in a new way to solve issues which had blighted earlier buildings.

Walls were constructed with an internal cavity, an air gap which would help them resist the effects of wind and rain. The outer facing of brick was just to seal the building from the weather while the internal leaf, often made from breeze blocks, carried the load of the building. Damp-proof courses were standard with a line of bitumen or similar products set into the wall which helped them resist rising damp.

Foundations began to be dug deeper than before especially in areas prone to ground movement and concrete was widely used under the building to create a more stable base than on Victorian houses.

Roofs were generally steep-pitched and covered with heavy clay tiles; a sturdy construction which not only resisted the worst of the weather but also provided the owner with a spacious loft.

A Housing Revolution

These new homes also provided a roomy, bright and airy interior. Even the smallest featured a living room, separate kitchen, hot and cold running water, a bathroom and a flushing internal toilet; a revolution for families moving from cramped, unsanitary urban slums.

Curving and circular planned roads were not just a novelty but designed so all houses would receive sunlight during the day through the wide windows which were fitted in most homes.

Despite the incredible improvement in the standard of accommodation for the lucky few moving out of the slums, many discovered the rents still were too high. They also found the rules enforced by council inspectors irritating and the fact they were stuck in remote suburbs away from their friends and family was unbearable for some.

A few even rejected their new houses and slipped out at night to go back to their old homes.

The Middle Class

Those from a more affluent background who had survived the horrors of the war also had the potential to improve their accommodation.

Cheap mortgages allowed many to buy their own homes; before the First World War only around 1 in 10 owned their home, thirty years later it would be nearer 1 in 3.

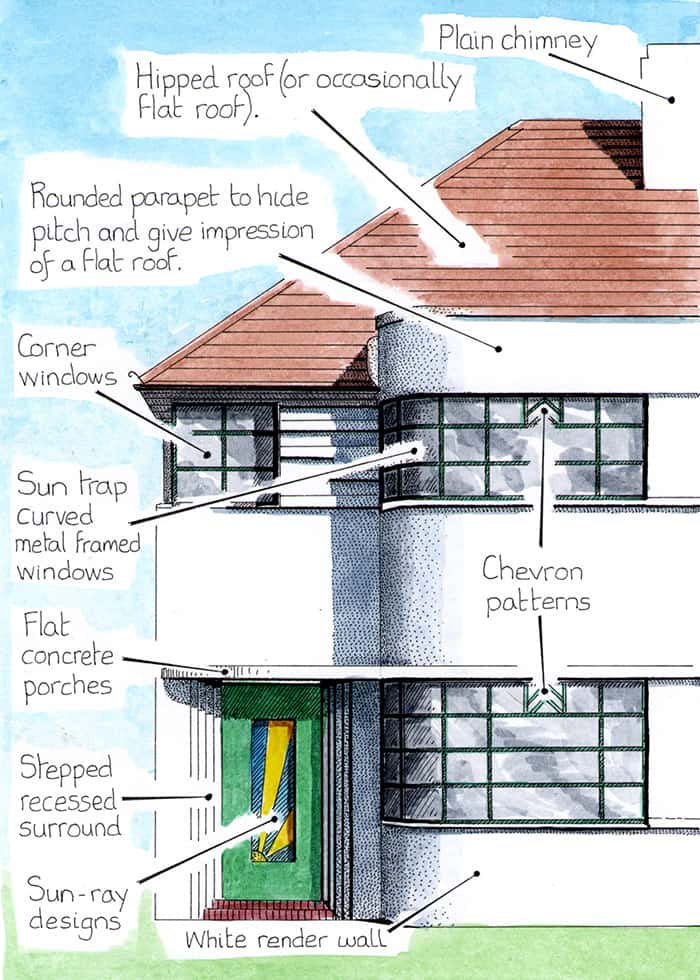

The terrace had fallen from fashion and the semi or detached home with a steep hipped roof (slopes on all four sides), an arched recessed doorway, with a little window to the side illuminating a wide hall was distinctive for the period.

Inside they provided a separate living room, dining room and kitchen usually with three bedrooms upstairs and a bathroom and flushing toilet.

With a large garden to the front and rear of the property those who could afford a car had space for a driveway.

A few of the most modern homes even had a garage built into the structure while freestanding ones could be bought flat packed and erected to the side of the house.

Architectural Fashions

The inter-war years also played witness to dramatic shifts in architectural fashions.

Previous housing had been decorated in forms which were based upon historic styles, with Classical, Tudor, Gothic, and Queen Anne decorative details applied to virtually any form of a building.

Now, the more adventurous private buyer could invest in homes built in a variety of modern styles which today we tend to group together under the banner Art Deco.

Houses and flats with plastered plain walls imitating the fashionable concrete, long metal-framed windows, simple geometric patterns and bays with curved ends reflected exciting new designs from Europe and the United States.

Some were even fitted with flat roofs, optimistically advertised as sun-traps, despite our cold and wet climate.

By the time the Second World War broke out, there was still a demand for new housing and the slums were only partially cleared.

However, the work done by local authorities and private builders had not only begun the process to reverse the problem but had also created new forms of buildings, methods of construction and an approach to the design of estates which would continue to shape housing in the 1950s and 60s and set expectations which still influence the design of estates today.