The Terraced House Through Time: From the Great Fire to the Edwardians

-

by Trevor Yorke

Trevor Yorke is an experienced author and artist who specialises in period architecture. For more information and to see a selection of his books you can visit his website, here.

Terraced Housing

In a country where privacy is demanded and gardens are treasured but urban space is limited and land expensive, the terraced house has long been the most economical solution for housing.

From the graceful stone-faced Georgian crescents and white painted Victorian townhouses in exclusive city locations to the monotonous rows of humble red brick homes which characterise many old industrial areas, the terrace is devoid of social status and seems to simply vary in size to meet the demands of its owners.

However, the terrace has developed over the centuries in response to social changes, industrial growth and catastrophic disasters.

By looking at the form, style and details on a terrace you can discover their age and the type of people they were originally built for.

The Great Fire of London

When Thomas Farriner’s bakery in Pudding Lane, London, caught fire one Sunday morning in September 1666 few would have thought that this would result in a chain of events which would change the face of British housing.

Urban areas had developed with little control over their planning and areas became crammed with timber and thatch buildings overhanging narrow winding streets.

This disorganised maze of ramshackle properties created a flammable cocktail which fuelled the Great Fire of London. The vast scale of this conflagration finally forced the authorities to lay down legislation to help prevent it occurring again.

A series of acts and regulations, at first in the Capital and later out in the provinces, ensured walls were made from brick or stone, roofs tiled and party walls built so that fire could not spread along timbers in the roof.

Part of the process involved the establishment of different classes of building, their dimensions and even the width of associated streets. This helped shape the form of new terraced houses which would be built during the rebuilding of the Capital.

Design Features Through Time

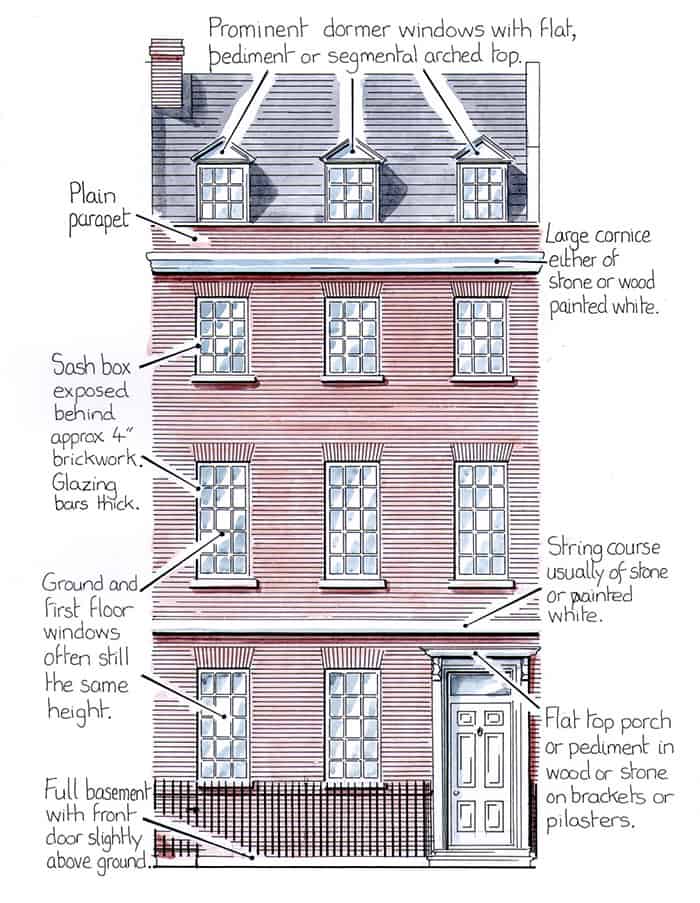

Some of the changes can be used to help date houses. For instance, sash windows which were introduced in the late 17th century were at first positioned flush with the outer wall until legislation from early in the next century forced builders to set them back four inches to reduce the risk of fire spreading along a facade.

They went further still from the 1770s when the outer frame or box had to be fully hidden behind the outer wall by which time they began to be fitted with thinner glazing bars and larger pieces of glass.

The Great Fire of London had occurred at a time when the recently restored monarchy had brought back with them from exile a taste for the Classical and the familiar form of terraced house evolved partly to reflect the desire for symmetry and fine proportions.

Although the door would ideally be placed in the middle, a centrally placed door would have left two thin rooms flanking it, so the entrance was placed to one side and the main entertaining rooms sited on the first floor above.

By the mid 18th century these first floor rooms would often be taller than the others with larger windows and decorative details to emphasise its importance.

An Early Georgian Terrace

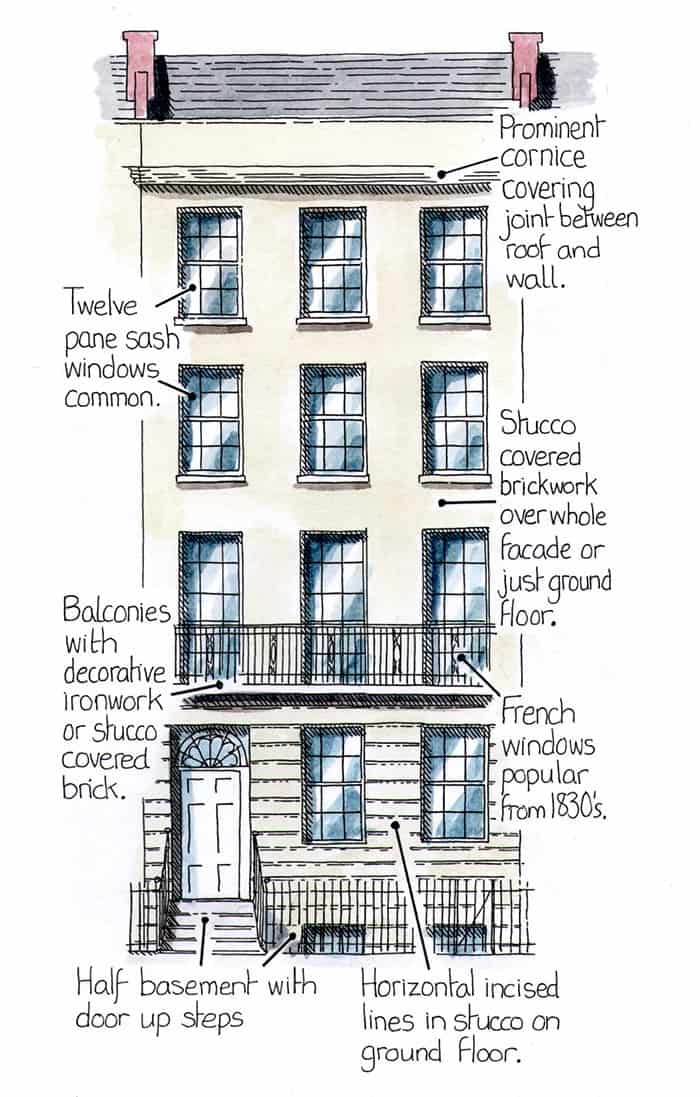

Initially, service rooms were in the basement below but from the second half of the 18th century it became more common for a half basement to be built which not only allowed more light into the rooms below but also meant the front door had to be accessed up a short flight of stairs making for a more impressive entrance.

This difference in form can help date early and late Georgian terraces.

A Late Georgian Terrace

Added to this was the greater number of household staff which needed to be housed hence terraced houses became taller often with four or five storeys and attic rooms above for servants accommodation. Up until the mid-Victorian period, fashionable Classical style terraces had their roofs hidden behind a parapet and the exterior covered in stucco (a smooth render coloured to imitate stone but now usually painted white).

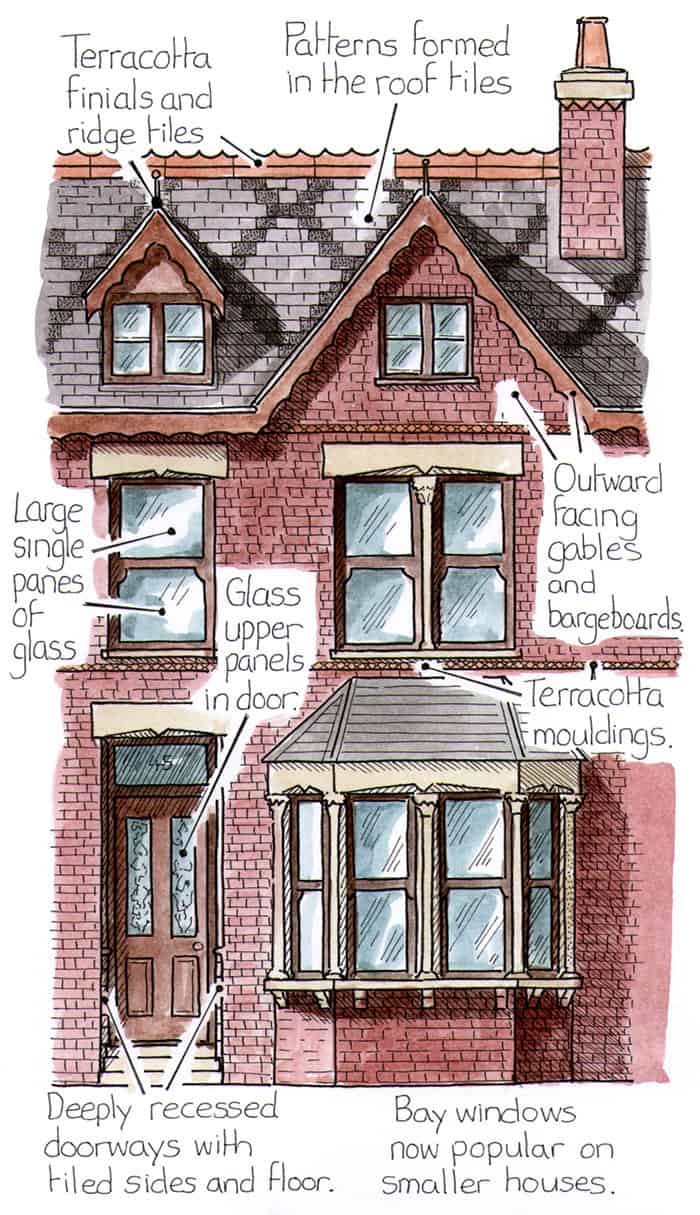

However, by the 1860s the popularity of the Gothic Revival resulted in many being built with a steeply pitched roof open to the front and exposed yellow or red brick walls.

They often featured a triangular gable end to one side and a pointed dormer windows set in the roof above to emphasise the asymmetry of this style.

The Early 19th Century

The main rooms in a large house had been flexible spaces with furniture moved around to suit different uses, but by the early 19th century there were more individual rooms with specific roles.

Added to this was the greater number of household staff which needed to be housed hence terraced houses became taller often with four or five storeys and attic rooms above for servants accommodation. Up until the mid-Victorian period, fashionable Classical style terraces had their roofs hidden behind a parapet and the exterior covered in stucco (a smooth render coloured to imitate stone but now usually painted white).

However, by the 1860s the popularity of the Gothic Revival resulted in many being built with a steeply pitched roof open to the front and exposed yellow or red brick walls.

They often featured a triangular gable end to one side and a pointed dormer windows set in the roof above to emphasise the asymmetry of this style.

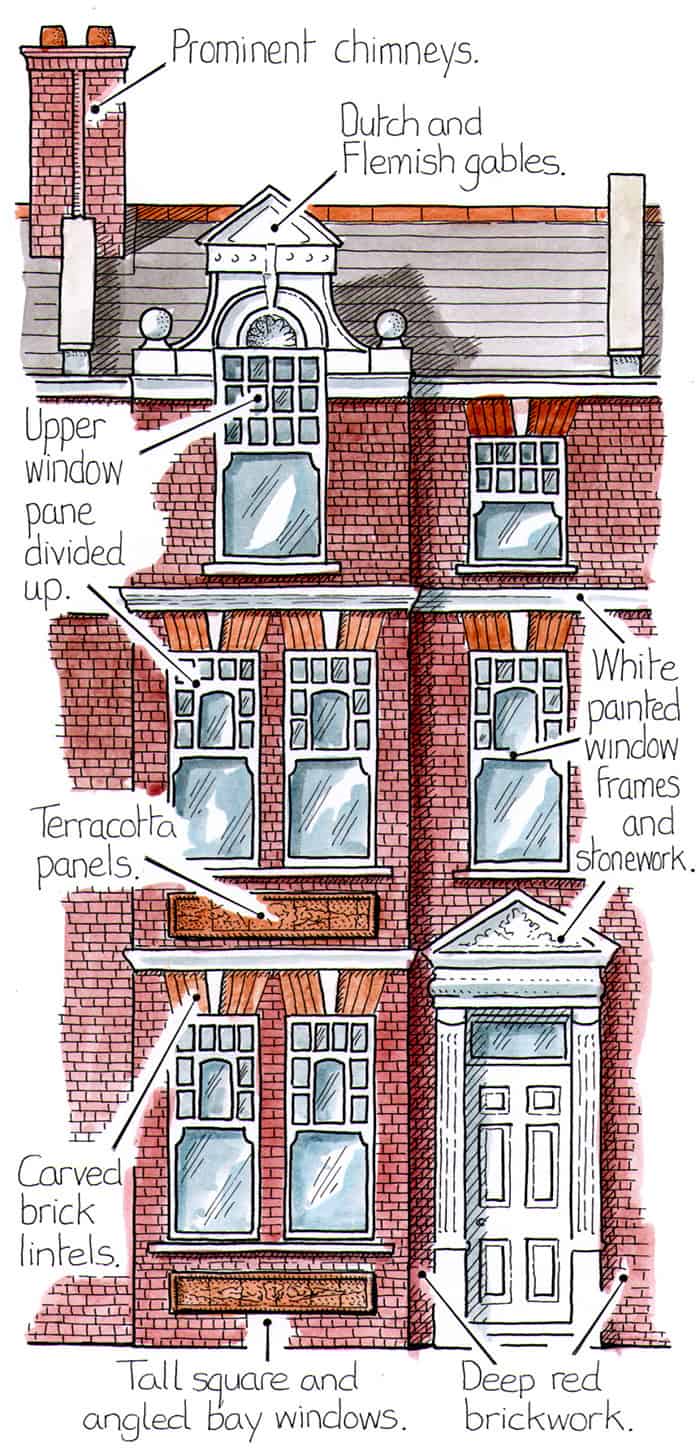

The Queen Anne Style

By the 1880 and 90s, the 'Queen Anne' and 'Arts and Crafts' styles influenced suburban terraces. Sash windows had their top pane divided by glazing bars and the upper half of walls covered in a rough finish render, mock timber framing or hanging tiles.

Edwardian Houses

Edwardian versions often featured white painted external woodwork on porches and balconies with chimneys emerging from the roof halfway down the slope rather than at the ridge.

There were few large-scale building companies in the 19th century so most of these terraces were built in short rows by different builders, or by the same one but with the next few houses only built after the previous ones had been leased out.

Dating a Terraced House

Today, a long row of terraces might appear all the same but look closer and you will see vertical joints and gaps in brickwork or slight differences in details which highlight different periods of building.

The photograph below illustrates this well. To the left, you can see a house built in the late 17th century whereas the house to the right was built in the late 18th century.

For the growing middle classes, more modest terraces evolved to which a few mass-produced details could be added to imitate the fashionable homes of the well off.

A squat two up two down terrace with the upper windows tight under the eaves was a popular form in the first half of the 19th century, but as income and expectations grew so terraces designed to attract the middle classes grew in height with taller rooms, a steeper roof and often a third storey or dormer windows so the loft could provide sleeping accommodation for a live-in maid.

You can often tell the date of these terraces from the extensions made to the front and rear. A single bay window on the ground floor room was popular in the 1850s and 60s, two storey bays became fashionable on this class of home later in the century.

Rear extensions were added at ground floor level to provide a scullery in early examples but from the 1870s they often had two storeys to create an extra bedroom above (these have usually been converted into a kitchen and bathroom today).

The front door on most of this class of terrace opens directly onto the pavement but as Victorians sought privacy builders created tiny walled spaces of a few feet in depth in front to imitate the large walled gardens of the finest houses.

By the Edwardian period this was a standard feature and in suburban areas allowed for a modest garden and tiled (often black and white) path to the front door which was now usually sheltered by a porch.

As working-class families began flooding into new industrial areas most found accommodation in a single room within a larger house or in cramped homes in the yards or around courts at the rear of them.

Builders and landlords began developing terraces for this class but as they sought to maximise their return they crammed as many houses into a plot as possible with little control from local authorities as to the overall planning of these rapidly expanding urban areas.

These new terraces took a variety of forms with different types popular in certain regions but the most notorious were the back-to-backs. These usually had just a small living room, a cellar, below, and a bedroom above and backed onto the house behind so there was no rear garden and you could not throw the windows open to ventilate the house.

For many residents, these poorly designed terraces were an improvement over what they were used to but with limited space, poor sanitation and a communal toilet many of these developments would later become slums.

Those in better-paid jobs might be able to rent a two up two down with their own privy in the rear yard, a form which became more widely available to working-class families by the end of the Victorian period as wages slowly improved.

However, for those trapped in the slums, there was little drive from the authorities to address the situation so it was down to benevolent individuals and charities to develop new forms of working-class housing.

They focused on building accommodation which provided through ventilation, running water, and a privy at the back of the yard.

Most back-to-backs and similar, early forms of working-class housing have long since been flattened although some of the better examples still survive in cities like Leeds or at the rears of large urban houses.